(C) 2012 Chia-Ying Ko. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

The earth is warming rapidly. Species around the world must adapt to the increasing heat and to the rapid rate of temperature change. Decision makers and managers must aid species to adapt and to keep up with the changes if they are not able to do so on their own. Special attention needs to be paid to small islands because they are at high risk for the loss of unique and threatened systems and species, and face habitat loss as a consequence of climate-induced rises in sea level. In this study, we examined 17 endemic avian species on the island of Taiwan. Bird observations from 1993 to 2004 were compared to modeled distributions for 2020, 2050, 2080 and 2100. We used 5 general circulation models (CCCMA, CCSR, EHAM4, GFDL, and HADCM3) for the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change A2 and B2 scenarios. Results show that the distributions of 15 out of 17 species are predicted to shift up in elevation with warming. As the lower distributional limits contract to higher elevation, the upper edge of their current distributions cannot shift up in elevation because they were already near or at the tops of the mountains. Consequently, their distributions are predicted to shrink over time. The median elevation of each of these species’ distributions is higher than the median elevation of all available habitats on Taiwan. In addition, we find that a few common species are predicted to become rare species under climate change. Two of the 17 species examined are not near the tops of the mountains and are the only species that have median elevations of their distributions lower than the median of all available habitats on Taiwan. These 2 species are predicted to expand the upper-elevation distribution limit but not to contract the lower-elevational limit, which results in a widening of their distributions. Hence, we suggest that the median elevation of a species’ current distribution plays a key rule and can be further used as an index of the response birds most likely will exhibit as the temperature increases.

Climate change, projection distribution, island species, endemism, geographic patterns

The earth’s ambient temperature is increasing at an alarming rate and magnitude. These increases are producing changes in natural systems (

The risk of extinctions worldwide will likely be exacerbated by climate change that occurs too rapidly to allow species to adapt (

An appropriate scale and list of environmental factors are both key factors in the prediction of species distributions. Investigating scaling questions is worthwhile on both islands and continents. The choice of a spatial scale to be used in species-distribution models plays an important role in model performance and follow-up applications. However, the available environmental data and species-occurrence records often limit the choice of scale, especially with respect to finer scales (

Selecting appropriate environmental factors for investigating species distribution models is critical when investigating the suitability of models that can be used to aid in conservation efforts for different species. Numerous studies have assessed many environmental factors. These studies have calculated and examined the individual contributions of different environmental factors and their effects on the distribution and abundance of different taxa (

To provide a comprehensive perspective on the effects of future warming, studies often use predicted changes in temperature and precipitation to simulate the effects of future warming. Various models of future temperature and precipitation have been created under different assumptions about the trajectory of global emissions. The variability in projected precipitation among the different models is quite a bit larger than that for projected temperature. On the island of Taiwan, many factors, including occurrences of typhoons and ocean cycling, cause large variations in precipitation. These variations coupled with the model variations make it difficult to forecast general or specific patterns in the magnitude of future precipitation. Moreover, the temperature showed higher contributions than the precipitation on distributions of the Taiwanese endemic bird species (

Studies linking the current and future distributions of species are expected to yield useful suggestions about possible indicators for use as reference points for conservation efforts in response to climate change. Current literature on the projection of species distributions, however, involves active debates about questions including uncertainties in species’ dispersal abilities, migration rates, and area sizes of fundamental and realized niches occupied by species (

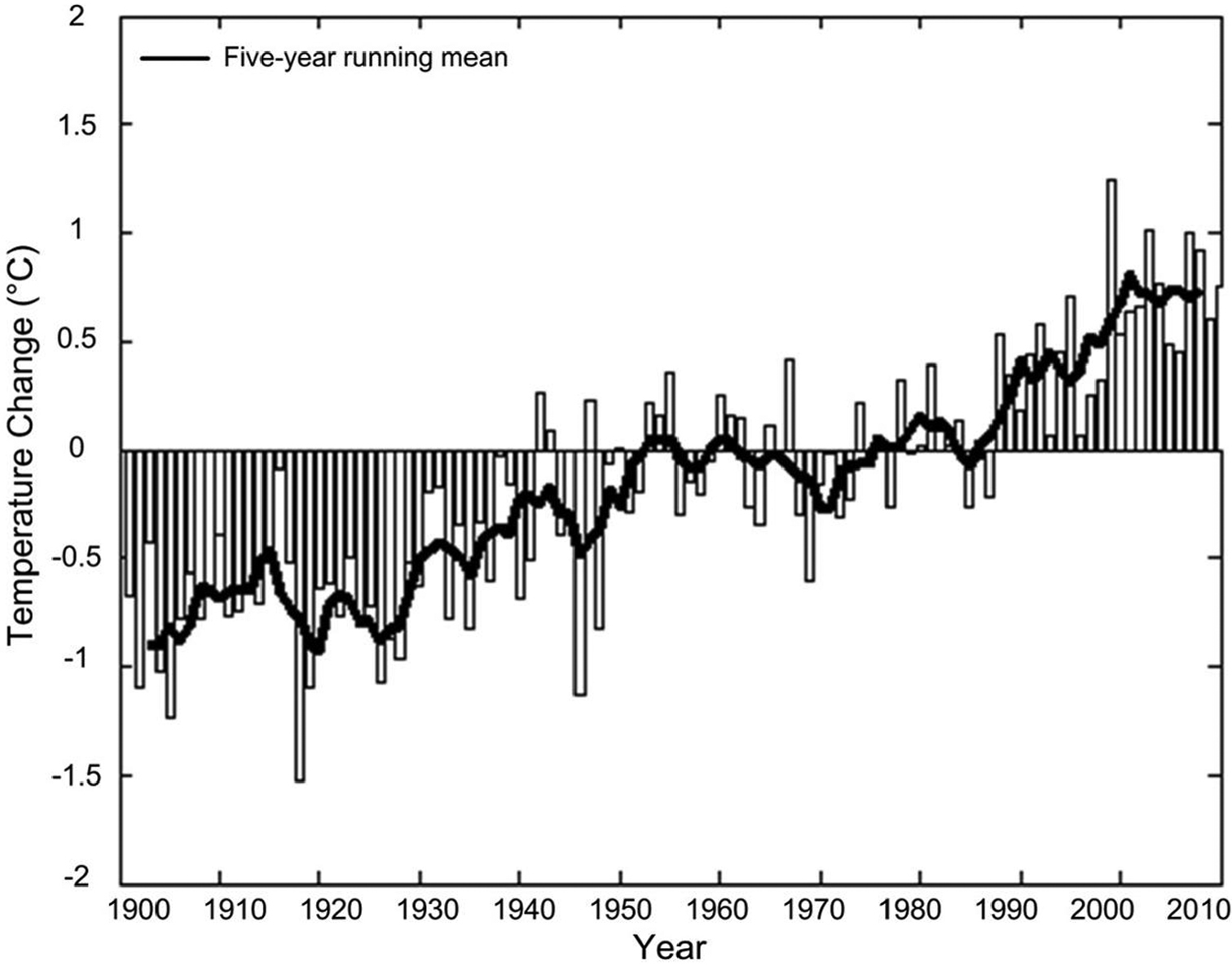

The island of Taiwan serves as a representative island for island studies generally. Taiwan, located at the boundary between the tropics and the subtropics, offers a range of topography and biodiversity. Global warming obviously impacts the island: from 1900 to 2010, island temperatures increased by approximately 1.6°C, an increase of 0.13–0.15°C per decade (Fig. 1). Current and projected increasing damage and irreversible loss of unique and threatened natural systems have attracted attention because Taiwan is a prioritized conservation hotspot in Asia (

The increase in the observed annual mean temperature on Taiwan from 1900–2010. Temperature change in each year was calculated by comparison of the annual mean temperatures averaged from 1990 to 1999.

We assumed that species distributions will shift in elevation in concert with warming temperature. Depending on the physiological ecology of the species in question and compiling studies projecting species ranges (

We obtained occurrence data for the 17 Taiwanese endemic species from a 12-year inventory of avifauna from 1993 to 2004 (

We obtained monthly mean temperature data from the Central Weather Bureau of Taiwan form 1990 to 1999 at 25 long-term climate-monitoring stations and 102 locations where there were only temperature recording equipment and auto-rain gauges of the Central Weather Bureau of Taiwan. We averaged temperature in those 10 years in each grid cell and used these as a surface showing of current annual mean temperature. High-resolution gridded climate data are required for spatial analysis of a small region with complex terrain and diverse climate states. The data-assimilation method, a technique using statistical analysis and interpolation to integrate irregularly distributed observation into regular model grids (

To make sure the temperature data used in this study were the most suitable and representative, we compared temperature data from a widely used global climate dataset WorldClim (http://www.worldclim.org/ ) developed by

We obtained projected temperature trends, which had been specifically and locally downscaled to the 1×1km fine resolution in Taiwan by the same regression-based statistical downscaling approach (

The A2 and B2 scenarios were treated as antithetical frameworks. Taken together, they provided individual alternative scenarios for ways in which the future might unfold, according to the IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios in 2007. The two scenarios were derived from different assumptions about the release of greenhouse gases and aerosols into the atmosphere. They are used to explore future demographic, social, economic, technological and environmental developments on a global scale (

The original data from the GCM scenario-run outputs, adjusted for 1990s means, were first downscaled to local weather stations. They were then further adjusted by linking the normalized probability distribution functions of deviations of the monthly mean climate parameters. Finally, a linear interpolation method was used to generate interpolated climate-change surfaces. These surfaces gave values that, added to observed base temperatures, yielded the projected temperatures. Five projected-temperature models (i.e. CCSR, CCCMA, ECHAM4, GFDL, and HadCM3) for each of the A2 and B2 scenarios were used to predict the study species’ future distributions.

We used four temporal snapshots of the future changes in species distributions: 2020, 2050, 2080, and 2100. These years represented separate short-term, mid-term, and long-term climate-change influences on species distributions. To avoid chaotic weather fluctuations in the projected temperatures in one year, we used the average temperature from the prior 10 years for each year (e.g., the temperature projected for 2020 was calculated from 2010–2019).

Model use and statistical analysisA maximum-entropy approach (i.e., Maxent) (

Species’ current distributions given in

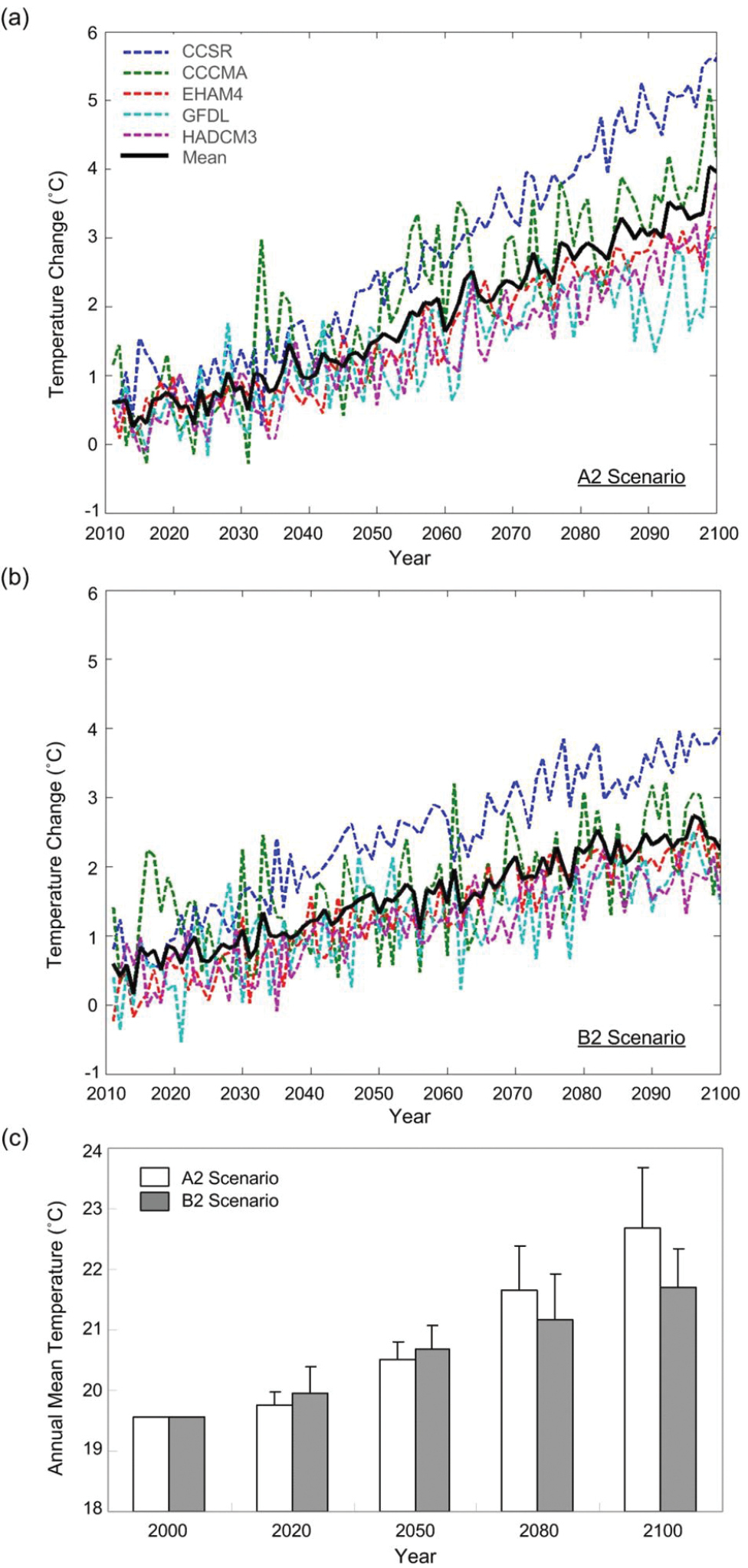

The projected future temperatures in Taiwan generated by the five models for the A2 and B2 scenarios showed increasing trends (Fig. 2a, 2b). The projected temperature by the five models for each temporal snapshot were different between A2 and B2 scenarios (p>0.05 in 2020 and 2050 and p<0.05 in 2080 and 2100) (Fig. 2c). In 2020 and 2050, projected B2 values were higher than those of A2, whereas the values in 2080 and 2100 showed A2 averages higher than B2. The averaged values of the projected increase in temperature ranged from 0.2°C to 3.1°C for the A2 scenario from 2020 to 2100, respectively, and the corresponding range for B2 increased from 0.4°C to 2.2°C, respectively.

Changing temperature patterns in Taiwan. a projected temperature for 2010–2100 from five general circulation models (CCCMA, CCSR, EHAM4, GFDL, and HADCM3) under the A2 emission scenario b projected temperature for 2010–2100 from five models under the B2 emission scenario, and c average projected temperature from four temporal snapshots, 2020, 2050, 2080, and 2100. The temperature in 2000 is presented for the current climate. The temperature change is from the averaged annual mean temperature from 1990 to 1999.

Fifteen of the Taiwanese endemic bird species were projected to decrease in distribution by 2100, whereas two species, the Styan’s Bulbul (Pycnonotus taivanus) and the Taiwan Hwamei (Garrulax taewanus), were predicted to increase (Table 1). A comparison of the actual observed elevation ranges and medians showed that the two “increasing-distribution” species occupied ranges whose median elevation was below the overall median elevation of Taiwan (Table 1).

Seventeen Taiwanese endemic bird species that show changes in the % of Taiwan grip boxes where the species was present (i.e., positive or negative slope) during 2020–2100 under the A2 and B2 projected scenarios and grid features of the elevation of their distributions.

| English Name | Scientific Name | Increasing/Decreasing Distribution (Slope) | Species’ Currently Occupied Elevation (m) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 scenario | B2 scenario | Range | Difference | Median | IQR* | ||

| Taiwan | 0-3707 | 3707 | 381 | 1194 | |||

| Decreasing-Distribution Species | |||||||

| Taiwan Barbet | Megalaima nuchalis | -11.0 | -7.6 | 2–2956 | 2954 | 415 | 629 |

| Formosan Whistling-Thrush | Myophonus insularis | -5.6 | -3.4 | 7–2764 | 2757 | 720 | 890 |

| Taiwan Partridge | Arborophila crudigularis | -5.5 | -3.3 | 18–2630 | 2612 | 1125 | 933 |

| Formosan Magpie | Urocissa caerulea | -4.3 | -2.8 | 7–1487 | 1480 | 406 | 439 |

| White-eared Sibia | Heterophasia auricularis | -4.3 | -2.5 | 7–3358 | 3351 | 1425 | 969 |

| Swinhoe’s Pheasant | Lophura swinhoii | -4.1 | -2.4 | 100–2457 | 2357 | 1389 | 760 |

| Taiwan Yuhina | Yuhina brunneiceps | -4.1 | -2.4 | 7–3358 | 3351 | 1587 | 893 |

| Steere’s Liocichla | Liocichla steerii | -3.3 | -1.9 | 98–3155 | 3057 | 1639 | 799 |

| Taiwan Bush-Warbler | Bradypterus alishanensis | -3.2 | -1.9 | 147–3422 | 3275 | 2179 | 969 |

| Collared Bush-Robin | Tarsiger johnstoniae | -2.9 | -1.8 | 100–3707 | 3607 | 2284 | 699 |

| Yellow Tit | Macholophus holsti | -2.9 | -1.6 | 7–2815 | 2808 | 1622 | 615 |

| White-whiskered Laughingthrush | Garrulax morrisonianus | -2.8 | -1.7 | 100–3707 | 3607 | 2338 | 706 |

| Taiwan Barwing | Actinodura morrisoniana | -2.8 | -1.6 | 7–3015 | 3008 | 2102 | 597 |

| Mikado Pheasant | Syrmaticus mikado | -2.8 | -1.6 | 100–2979 | 2879 | 2121 | 623 |

| Flamecrest | Regulus goodfellowi | -2.6 | -1.7 | 378–3707 | 3329 | 2573 | 654 |

| Increasing-Distribution Species | |||||||

| Styan’s Bulbul | Pycnonotus taivanus | 3.9 | 1.6 | 3–2321 | 2318 | 169 | 259 |

| Taiwan Hwamei | Garrulax taewanus | 3.2 | 1.2 | 2–2735 | 2733 | 276 | 420 |

*IQR = interquartile range

Estimates of the change (i.e., slope) in the percentage of the distribution areas over the four snapshot years and estimates of the lowest and highest observed elevation of individual species showed no significant difference among the seventeen species (p>0.1) (Table 1). The species-occurrence elevations of the 15 “decreasing-distribution” species were divided into current low- to mid-elevation and mid- to high-elevation species. The division between these two elevations was chosen to be at 1600 m based on the species’ currently occupied elevation (Table 1). The current low-to-mid-elevation species (7 species) exhibited a significant decrease between 2020 and 2100 under both A2 and B2 scenarios (p<0.01) while no significant decrease in the current mid- to-high-elevation species (8 species) (Table 2).

Differences in the percentage of future projected species present in areas of Taiwan between 2020 and 2100 for 15 endemic bird species that showed an expected decrease in distribution as result of climate change. The species’ distributional altitudes were based on occurrence records using the 1600 m median elevation as a threshold for determining current low-mid- (LM) and mid-high-altitude (MH) species. The current conservation status of a species was characterized as common (C), uncommon (U) or rare (R), as defined by

| English Name | Distributional altitude |

Current Status |

% of Distribution Areas Decrease between 2020 and 2100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 scenario | B2 scenario | |||

| Taiwan Barbet | LM | C | 32.1 | 23.6 |

| Taiwan Partridge | LM | C | 16.0 | 10.4 |

| Formosan Whistling-Thrush | LM | C | 16.3 | 10.8 |

| White-eared Sibia | LM | C | 12.2 | 7.6 |

| Taiwan Yuhina | LM | C | 11.6 | 7.3 |

| Formosan Magpie | LM | U | 12.8 | 8.9 |

| Swinhoe’s Pheasant | LM | R | 12.0 | 7.8 |

| Steere’s Liocichla | MH | C | 9.4 | 5.7 |

| Collared Bush-Robin | MH | C | 8.5 | 5.4 |

| White-whiskered Laughingthrush | MH | C | 8.1 | 5.2 |

| Yellow Tit | MH | U | 8.4 | 5.0 |

| Taiwan Barwing | MH | U | 7.9 | 4.8 |

| Taiwan Bush-Warbler | MH | U | 9.2 | 5.8 |

| Flamecrest | MH | U | 7.7 | 5.0 |

| Mikado Pheasant | MH | R | 8.0 | 4.9 |

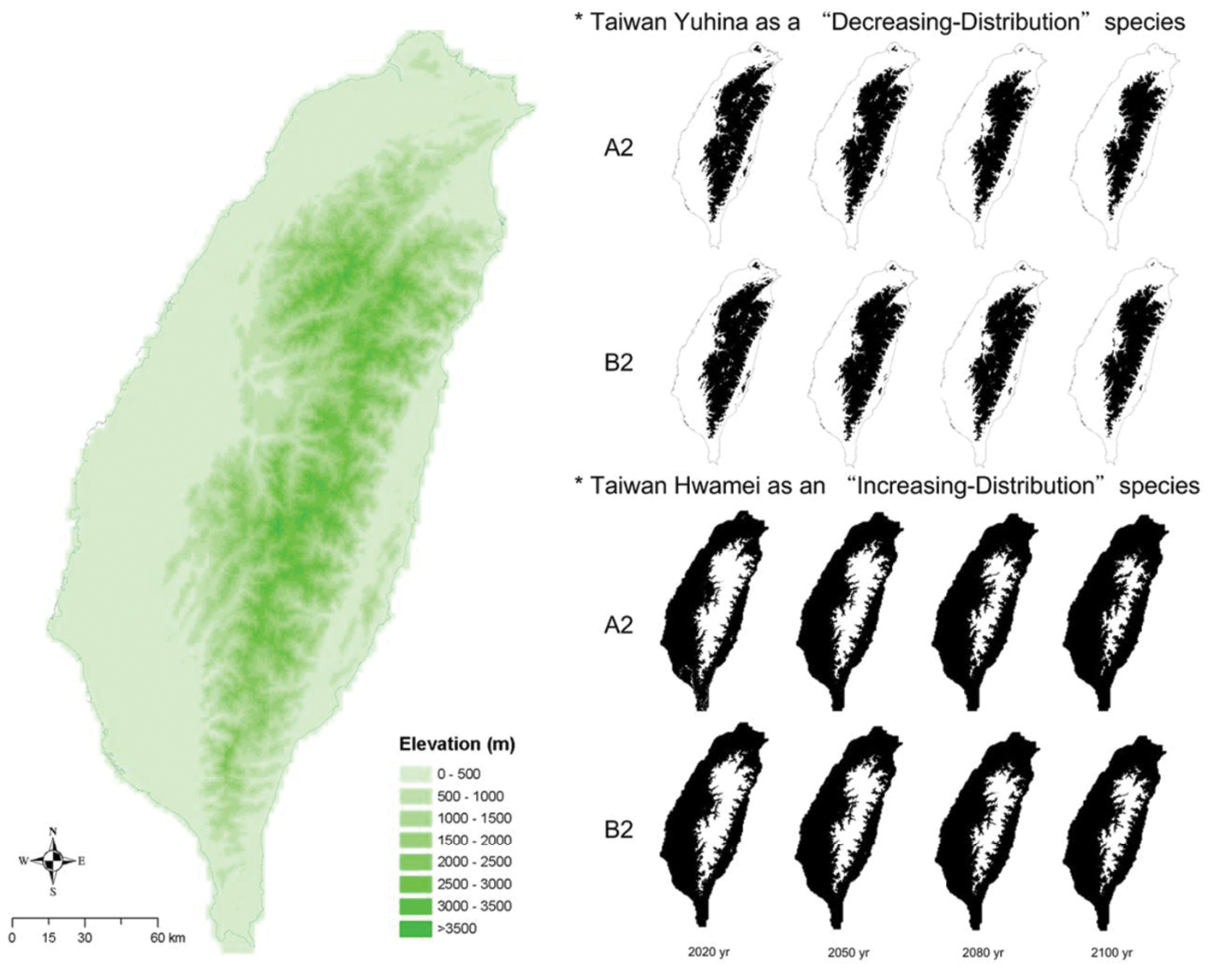

The geographical changes in the species’ future distributions in both the A2 and B2 scenarios indicated that the “decreasing-distribution” species would shift towards high- elevation areas and contract along warming boundaries. The result of this shift would be an overall decrease in distribution (Fig. 3). For example, the Taiwan Yuhina showed a monotonic contraction of its distributions from 2020 to 2050, to 2080, and to 2100 (Fig. 3). The general plots of all 15 “decreasing-distribution” species showed that the species would have greater distributional changes in Western Taiwan than Eastern Taiwan, owing to the relative steepness of the topography on the eastern and western sides of the island. The “increasing-distribution” species would not change their distributions by shifting their lower distributional boundary to a higher elevation. Rather, the projections show they would maintain their lower boundary and shift their upper boundary to a higher elevation. The Taiwan Hwamei (Fig. 3) is an example of this pattern of distributional shift.

Elevation maps of Taiwan and geographic changes with warming temperature in the projected distributions of Taiwanese endemic bird species in 2020, 2050, 2080, and 2100. The Taiwan Yuhina (Yuhina brunneiceps), an example of a “decreasing-distribution” species (the right-hand upper eight maps), would decrease in distribution as it shifts to higher elevations. The Taiwan Hwamei (Garrulax taewanus), an example of an “increasing-distribution” species (the right-hand lower eight maps) would increase its distribution by moving to higher elevations. The black areas are species’ projected-present distributions, whereas the white areas are species’ projected-absent distributions.

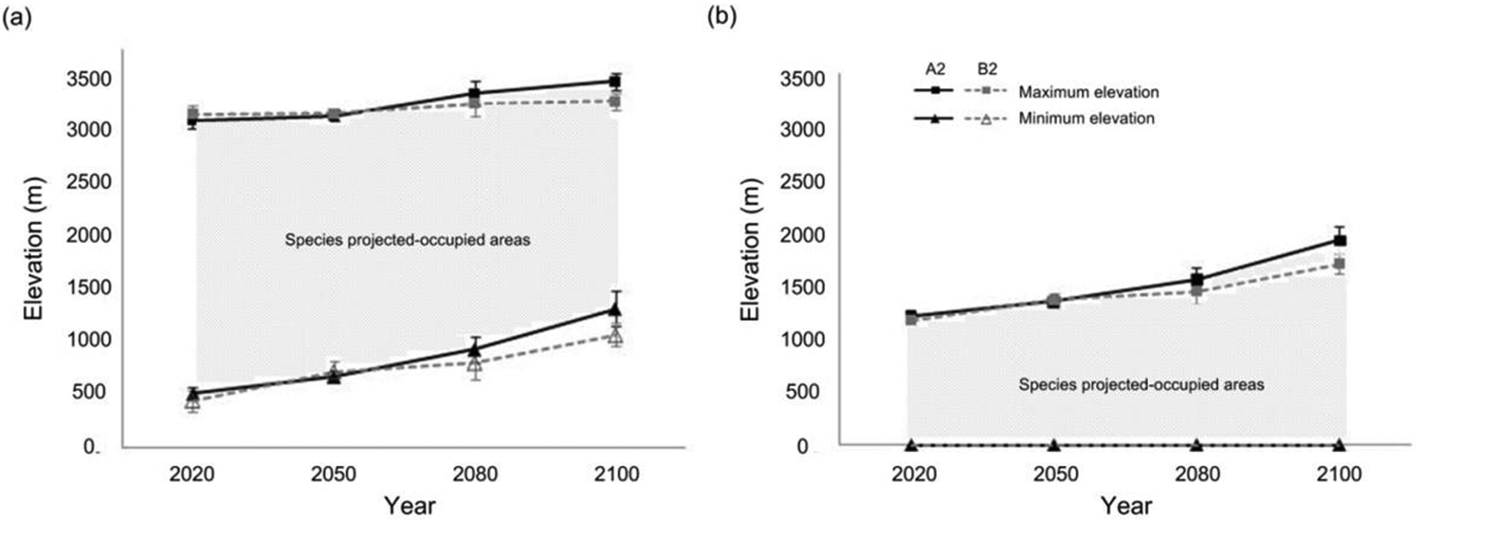

Changing trends in species’ projected occupancy of maximum and minimum elevations revealed differing shift rates that could further explain why a species could increase or decrease (Fig. 4). Under both the A2 and B2 scenarios, the “decreasing-distribution” species’ shift in minimum elevations from 2020 to 2100 would occur more rapidly than the corresponding change in maximum elevations. Together, these changes would cause species’ distributions to shrink (Fig. 4a). However, the “increasing-distribution” species would have an unchanging minimum elevations but higher maximum elevations than in a previous temporal snapshot. These changes would broaden their distribution areas (Fig. 4b).

Changing trends in species’ projected-occupied maximum and minimum elevations. A species a with faster shift rates at minimum elevations than at maximum elevations would become a “decreasing-distribution” species (example: Taiwan Yuhina), and b those with a stable minimum elevation and an increasing maximum elevation would become an “increasing-distribution” species (example: Taiwan Hwamei) in response to climate change.

Anthropogenic climate change is causing an increase in temperatures in Taiwan. Our results indicated that the 17 endemic bird species could have changes in their distributional range as a result of continued warming. All 17 species show changes in the upper elevational distributional limits shifting upward. The species with their medians higher than that of all of Taiwan would contract their lower-elevation boundaries with increases in temperature, while species with lower medians than that of all of Taiwan would extend their higher-elevation boundaries but not contract their lower boundaries. Because this work was performed on an island, we were able to examine the changes in the percentage of the distributional areas for each species.

As the temperature warms, the assemblages of species present in a given place are likely to change over time (

Using current environmental correlates of a species’ distribution to project its future occurrence by using five different models assumes that the species would exhibit the same behavior regardless of the type of habitat into which their distribution would expand. This assumption could certainly hold for some but not all species. This caveat must be considered in the case of the two species we examined the projections that showed expansion of their distributions. Indeed, the projected expansion may not be possible because of the type of habitat available. Additionally, land-use change could significantly imperil the ability of a species to expand its range (

The projected expansion could indeed be overly optimistic about places in which the species could inhabit. Various ecological and geographical barriers across space are other key points, in addition to climate, which affect species dispersal and distribution and habitat connectivity. For instance, the Styan’s Bulbul is currently restricted in distribution to a narrow area of eastern Taiwan. According to its projected geographical pattern, this species could expand to western Taiwan and become an “island-widespread” species instead of a “regionally-widespread” species. This expansion would require that the species increase its distribution across or around the Central Ridge Mountains of Taiwan in response to climate change. According to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) research on phylogeography in Taiwan show several species, such as Japalura swinhonis, Rana limnocharis, Gekko hokouensis, Mus musculus, Rhacophorus taipeianus, and Rhacophorus moltrechti, are divided into multiple small distributional populations by the Central Ridge Mountains (

In addition, based on the projected distributions, the Styan’s Bulbul and the Taiwan Hwamei will likely occupy their original low-elevation habitats in addition to expanding to higher-elevation areas. At some point, however, the temperature could become so warm that the low-elevation heat could lead this species to abandon its original lowland habitats and move up in elevation.

Potential shifts in species distributionsThe above-mentioned caveats notwithstanding, our results suggest possible elevational changes owing to increasing temperatures. Based on the observed records, the 17 species had ranges spanning 1480m in altitude for the species with the narrowest elevational range. The widest range is 3607m (Table 1). The species at these two extremes showed the same type of distributional change. The distribution of the species with the narrowest range (i.e. Formosan Magpie, Urocissa caerulea) is projected to decrease in size by 12.8% and 8.9% in the A2 and B2 scenarios respectively. The distributions of three other species had large decreases in size even though they had wider elevational ranges (Table 2). This result does not entirely agree with recent findings by

The median elevation occupied by species, relative to the value of median elevation for Taiwan as a whole, exhibits a pattern of changes in the projected future distributions. The species with their median elevation lower than the overall medium of Taiwan are projected to expand their distributions, whereas those species with medians higher than that of Taiwan are projected to contract upwards. Current distributional median elevation of a species, therefore, appears to be a new index for assessing species changing distributions with future warming.

Species with a current conservation status defined as common, uncommon, or rare based on the number of grids in which a species was seen, as defined by

The census data used in this study were collected throughout the island with a given location being censused 2–3 years on average. At some locations, however, there are longer term data sets. At these locations species distributional changes are occurring in the expected direction, i.e. upward shift in elevation. For instance, census data collected from 1992 to 2006 in Yushan National Park show that the richness of bird species increased at altitudes above 3500 m, because six montane species were found to have a higher upper distributional limit in 2006 than in 1992 (

Beside, the impacts of climate change on bird distributions between islands and continents could be different and is valuable to be further explored. Recent findings on California breeding land birds showed anticipated coastward and upslope shifts in distribution in response to a warming climate (

Ecological processes are usually gradual and can lead to continuous irreversible changes and evolutionary alterations. The four temporal snapshots in this study were selected to consider the possible reactions of species to a warming climate. Selecting several constant detection points (i.e., years) to evaluate climate-change impacts on species distributions in general may encourage vigilance among ecologists and conservation scientists. We must remember, however, that there are other forces than climate change that are acting on species. These forces include habitat destruction, invasive species, over hunting and harvesting, for example. A sharp threshold had been estimate to exist between habitat loss-patch occupancy and climate change, which pointed that the habitat (loss or destruction) threshold would occur sooner during climate change and species would suffer more risks (

Observed and projected distribution patterns show that the species studied are predicted to react differently to an increasingly warming climate, either increasing or decreasing their distributions. Our study demonstrated that current distributional median elevation of a species can be a new index for assessing species changing distributions in future warming with those having elevational medians below the elevational median of Taiwan would most likely have expanding distributions and those with medians above the available medians would most likely have contracting distributions. Indeed, endemic species deemed currently as common but have medians above the available medium could decrease their distribution so much that they become rare. Therefore, the possible future ecological response of current common species to climate change should not be ignored. Current common species could possibly have contraction of ranges, which could mean it might become a rare species when facing an increasing temperature. Therefore, understanding the possible effects of climate change on natural systems indeed provides more robust conservation and management practices to be determined by ecologists and governments. Species present distributional projections can be further strengthened with following long-term monitoring, targeted field-based observations and interdisciplinary experiments.

We thank the Endemic Species Research Institute in Taiwan for providing species data, many volunteers and researchers for collecting field data, Robert J. Hijmans for helping to clarify the climatic data and the two reviewers for insightful comments and constructive criticism on the manuscript. A National Science Council Grant in Taiwan 097IPFA0100038 partially supported (to C.-Y. Ko) this study. This research was sponsored by National Science Council and Council of Agriculture, Taiwan.