(C) 2012 Riikka Paloniemi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

One of the core challenges of biodiversity conservation is to better understand the interconnectedness and interactions of scales in ecological and governance processes. These interrelationships constitute not only a complex analytical challenge but they also open up a channel for deliberative discussions and knowledge exchange between and among various societal actors which may themselves be operating at various scales, such as policy makers, land use planners, members of NGOs, and researchers. In this paper, we discuss and integrate the perspectives of various disciplines academics and stakeholders who participated in a workshop on scales of European biodiversity governance organised in Brussels in the autumn of 2010. The 23 participants represented various governmental agencies and NGOs from the European, national, and sub-national levels. The data from the focus group discussions of the workshop were analysed using qualitative content analysis. The core scale-related challenges of biodiversity policy identified by the participants were cross-level and cross-sector limitations as well as ecological, social and social-ecological complexities that potentially lead to a variety of scale-related mismatches. As ways to address these cha- llenges the participants highlighted innovations, and an aim to develop new interdisciplinary approaches to support the processes aiming to solve current scale challenges.

Biodiversity conservation, environmental policy, governance, scale sensitivity, scale challenge, stakeholders, academia, EU

The year 2010 marked the deadline for the political targets to significantly reduce and halt biodiversity loss at global and the EU levels, respectively. Despite the efforts to date, assessments from global to local levels still document significant losses of diversity across spatial and temporal scales with potentially serious consequences in terms of provision of ecosystem services (

Mismatches between the scales at which ecological processes take place and the levels at which policy decisions and management interventions are made are amongst the main shortcomings of current biodiversity policy regimes (

Scale has been used in numerous ways: by referring to various sizes (small and large), to hierarchical structures composed by different levels, and to non-linear relationships taking place between and within various levels (

Different ecological processes and ecosystem functions occur at different temporal and spatial scales (

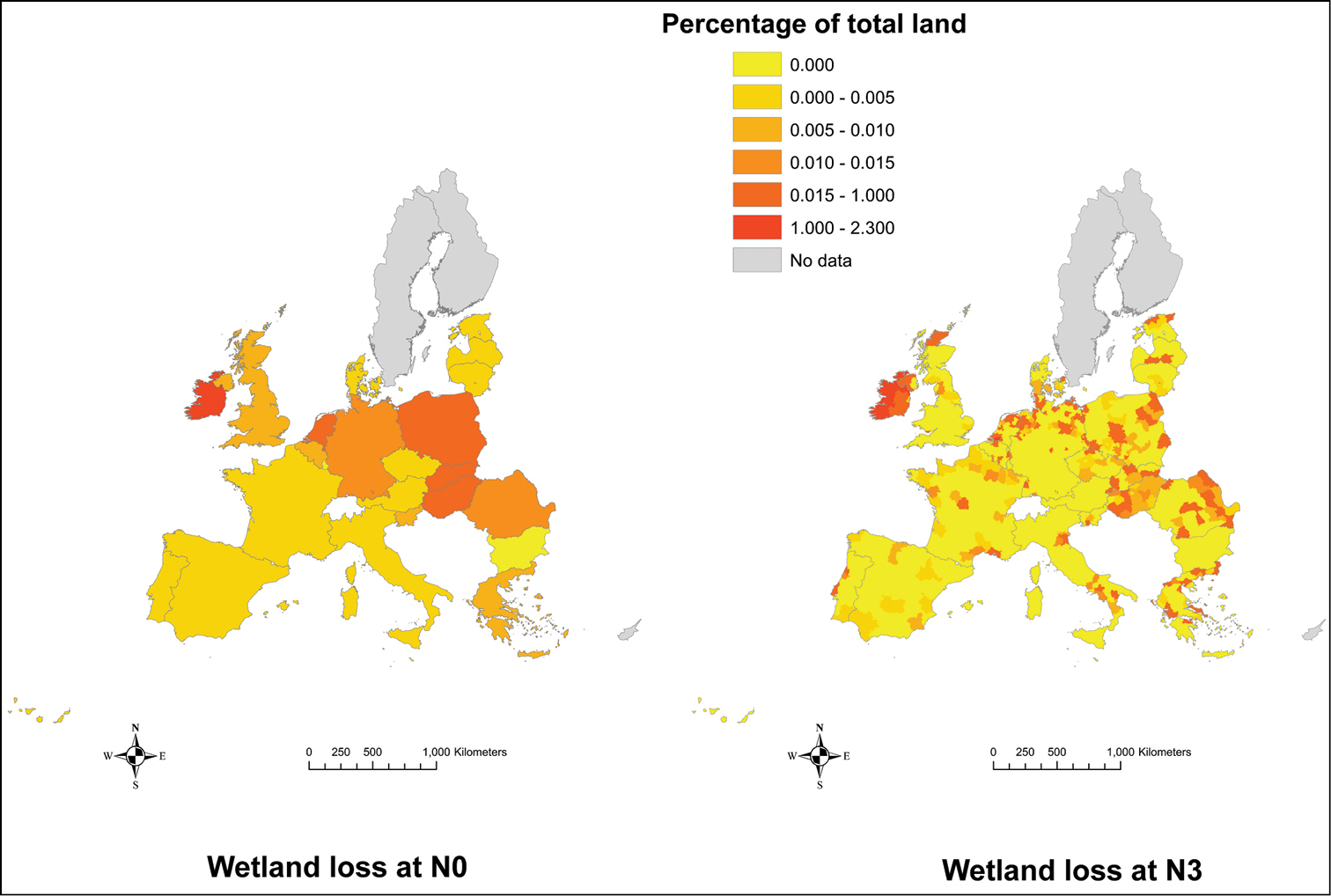

Changes in evenness of drivers: loss of wetlands across the EU.Abbreviation NUTS (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) refers to the regional classification within the EU, from country level (NUTS 0) to small regions (NUTS 3). The numbers show the hectares of wetland loss as a percentage of the total land in the respective NUT.

Biodiversity policies do not always take into account the scale-dependence of ecological phenomena and anthropogenic activities (

To add to the above described complexity, coordination between different policy sectors and jurisdictional levels has often proved to be inadequate. Characteristically, biodiversity governance still has little impact on other policies influencing economic activity and land use, such as the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP), Common Fisheries Policy, transport, planning or energy policies. Policies distantly related to biodiversity conservation often have goals contradictory to safeguarding biodiversity; for instance, a governmental priority for development plans has in many occasions resulted in planning policies which hinder the enforcement of conservation measures and sustainable land use rules (

To foster an open science–policy dialogue and to explore topical and innovative ideas for better integration of scale-related issues into biodiversity policy and governance in the EU and Member States, we invited 23 stakeholders to an expert workshop in Brussels. The participants were selected to establish a diverse group of stakeholders, covering both Member States and EU level. These participants included representatives from different Directorates-General (DGs) of the European Commission, from a number of environmental NGOs operating at EU level, and from Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Poland and UK. The national level participants were from ministries, national level NGOs, and sub-national level agencies implementing biodiversity policy.

We divided the stakeholders into four small groups, each including approximately 6–7 participants from the EU level institutions and from several Member States. Each group participated in two deliberative discussions, following brief introductions to the aforementioned scale issues. The first discussion explored how effectively existing policies address scale-related issues (at EU, national and sub-national levels). The second discussion aimed to explore new policy solutions for addressing the identified scale-related challenges. The discussions were facilitated and documented by some of the authors (2 researchers were participating in each group).

The discussion topics addressed scales, and whether it was a neglected issue in current biodiversity policy and governance, what were the key reasons for and barriers to addressing scale-related issues, and what the biodiversity challenges post-2010 are with specific attention to how addressing scales could help overcome the problems identified. Each discussion lasted c. 90 minutes and all discussions were recorded and reported by taking extensive notes. The discussions were analysed following the method of qualitative content analysis (

The stakeholders generally agreed that dealing with a number of different scales and their interactions simultaneously is a demanding, but important undertaking, and thus they supported the complex scale interpretation of

On one hand, the participants highlighted that current policy frameworks do not possess the necessary ‘scale-sensitivity’ to address the inherent complexity of ecological phenomena and to take into account species and ecosystem processes that operate at different scales, and especially their relationships with fragmentation and connectivity. By underlining these aspects, the participants paid significant attention to the need to more explicitly consider ecological scale in biodiversity governance (e.g.,

On the other hand, the participants stressed that when considering interactions between different governance levels, it is important not to ‘skip’ a level but rather to take the whole spectrum of governance into consideration. In many occasions, they emphasised the complexity involved in implementing multi-level and adaptive governance approaches especially when the focus lies on the management of both social and environmental change and uncertainty across scales (

Moreover, the participants often paid attention to the role of economic factors in the emergence of challenges in biodiversity governance. They identified the failure to link biodiversity (and its multiple values) to broader socio-economic benefits as a basis for conservation. It was argued that if biodiversity considerations are to be mainstreamed in decision making, then information about the complex roles of biodiversity and ecosystem services in supporting sustainable socio-economic systems at local, sub-national, national, and international levels should be generated and widely disseminated. This was considered as an important task, requiring a considerable amount of efforts in order to be reflected in the goals of conservation policies.

Cross-level and cross-sector limitationsThe participants identified difficulties in integrating biodiversity conservation objectives set by EU, national, sub-national or local levels into the objectives and decisions at other levels. The integration of objectives between local and sub-national levels on the one hand, and the EU level on the other, was considered as especially problematic. In particular, the participants often questioned the dominant position of the EU-level actors in developing the objectives for biodiversity policy. They argued that too often local level actors were overlooked in governance processes.

In many occasions, research participants argued that the main barriers to cross-level biodiversity governance are related to structural issues and relevant ‘governmental attitudes’. A recurrent statement in the discussions was that “the EU only talks to the national level”, referring to the difficulties in incorporating EU level goals into the sub-national and local policies and vice versa. The participants also pointed out the difficulties and apparent failures in taking national characteristics into account when developing and implementing EU policy instruments. For example, while the Habitats Directive forms a legislative basis for conserving species and habitats of EU interest it does not directly provide for protecting species and habitats important at national level (e.g., nationally threatened or endemic species). It also does not take into account the specific socio-economic contexts affecting conservation in different Member States. Furthermore, the implementation of EU policies falls under the competency of the Member States or the competency of the sub-national level (e.g. the Länder level in Germany). The latter case results in a divergence between implementing institutions at sub-national levels and national levels responsible for reporting on the overall Member States’ performance to the EU level, possibly leading to conflicts and confusion between actors. However, Natura 2000, the EU-wide network of conservation areas, and the main actions of National Biodiversity Action Plans, were seen in some cases as relatively successful in translating high-level aims (EU and national) into effective action at local levels. Moreover, EU policy frameworks, such as the Natura 2000 network or the Water Framework Directive, were considered by some participants as signs of a wider international reconfiguration and rescaling of power centres (including the reconfiguration of the EU’s role) and decision-making processes (see also

Despite different opinions regarding the above issues, the majority of participants agreed that even when there were local-level successes, these were too infrequently ‘scaled-up’ efficiently to national or EU levels. Thus, the findings underline a need to pay more attention to power positions of actors acting on various governance levels and having crucial roles in supporting and/or limiting successful processes of scaling up and down (see also

The participants also asserted that the numerous problems of biodiversity conservation are related to the failure to integrate biodiversity conservation into policies that affect the drivers of biodiversity loss. They argued that, for example, agricultural policies with intended pro-conservation aims could in practice function as drivers for biodiversity loss by supporting activities harmful to biodiversity. However, some of the research participants highlighted that the reason for these perverse effects by different sectoral policies, do not primarily lie in the limited coordination across policies or administrative levels, but rather in the tensions or even contradictions between various economic interests and conservation goals (see also

In order to tackle the identified scale-related challenges of biodiversity conservation, the participants made a number of recommendations.

They called for a new approach based on a more effective combination of fixed and flexible policy objectives. In particular, they argued that there should be a balance between designing ‘non-flexible’ societal and ecological objectives at the EU or Member State level and providing opportunities for strengthening the adaptive capacity to deal with uncertainty and change across scales. They highlighted the need for a better balance between maintaining the core policy objectives, and providing opportunities for stakeholders to get empowered and educated and to develop innovative solutions.

The participants also recognized that responding to current policy challenges requires a context-sensitive coordination in order to combine top-down policy design and implementation with bottom-up identification of problems and solutions in biodiversity conservation. Therefore, the need for coordination across scales and sectors should not undervalue the way that historical, cultural and local conditions and customs impact on biodiversity conservation creating different needs and opportunities in different settings.

With the aim of strengthening communication, the stakeholders proposed that cross-scale communication platforms would be essential for a new ‘biodiversity governance culture’ with more active, equal and meaningful local participation. In particular, social learning could be encouraged by creating platforms where stakeholders from different governance levels could share concerns and solutions (c.f.,

Finally, in order to improve cross-sector communication, the participants called for the development of new interdisciplinary approaches (

The science-policy discussion in the workshop proved to be a promising forum to present, negotiate and evaluate the research problems and findings between scientists, NGO representatives, policymakers and environmental authorities. The discussions between these actors and their results as presented in this paper illustrate a possible way of opening-up scientific discourses towards ‘extended peer communities’ (

We analysed the perspectives of policy makers, practitioners, and researchers with the aim of understanding the variety of views on current and emerging scale-related challenges of biodiversity conservation, as well as exploring opportunities for solving them. The participants of the workshop agreed that addressing the interconnectedness and interactions of scales in different ecological and governance processes is essential for achieving the goal to reduce biodiversity loss.

Our main finding is that scale-related problems, and potential solutions, are all about increasing our understanding of complexity and implementing this new knowledge. Dealing with a number of different scales and scale-mismatches emerging in biodiversity and its governance is unquestionably challenging; it requires an analytical and political framework that enables the simultaneous assessment of drivers, pressures and impacts as well as policy processes and practices at various scales and levels. Additionally, tackling scale challenges requires concrete steps towards the integration of biodiversity policies across governance levels and policy sectors and integrative governance institutions and networks. In the workshop, cross-scale communication platforms were considered as a promising forum to support communication and social learning. However, new, context-specific ideas are still needed to build dynamic governing structures and flexible policy processes to encourage more legitimate, fair, integrative and innovative biodiversity conservation practices.

We thank the participants of the workshop for sharing their experiences. SCALES is funded by the European Commission (FP7, grant 226 852,